In April 2003 Jørn Utzon, at the age of 85, was awarded the Pritzker Prize ─architecture’s ‘Nobel’. The citation reads: ‘There is no doubt that Sydney Opera House is his masterpiece. It is one of the great iconic buildings of the twentieth century, an image of great beauty which has become known throughout the world─a symbol for not only a city, but a whole country and continent’.

The presentation of the prize places Utzon in the pantheon of the greatest contemporary architects but marks a career that failed to reach its full potential following the traumas of building the Opera House.

Since it opened in 173 the Opera House has repaid its A$100 million cost many times over as a tourist attraction and as a cultural center. As a brand it is priceless. The story of its construction is one of triumph and tragedy.

It is Utzon’s masterpiece, yet he did not complete the building; the creation of the huge oversailing roofs was a magnificent feat of engineering and collaboration, but the design team split apart amidst misunderstandings and recriminations.

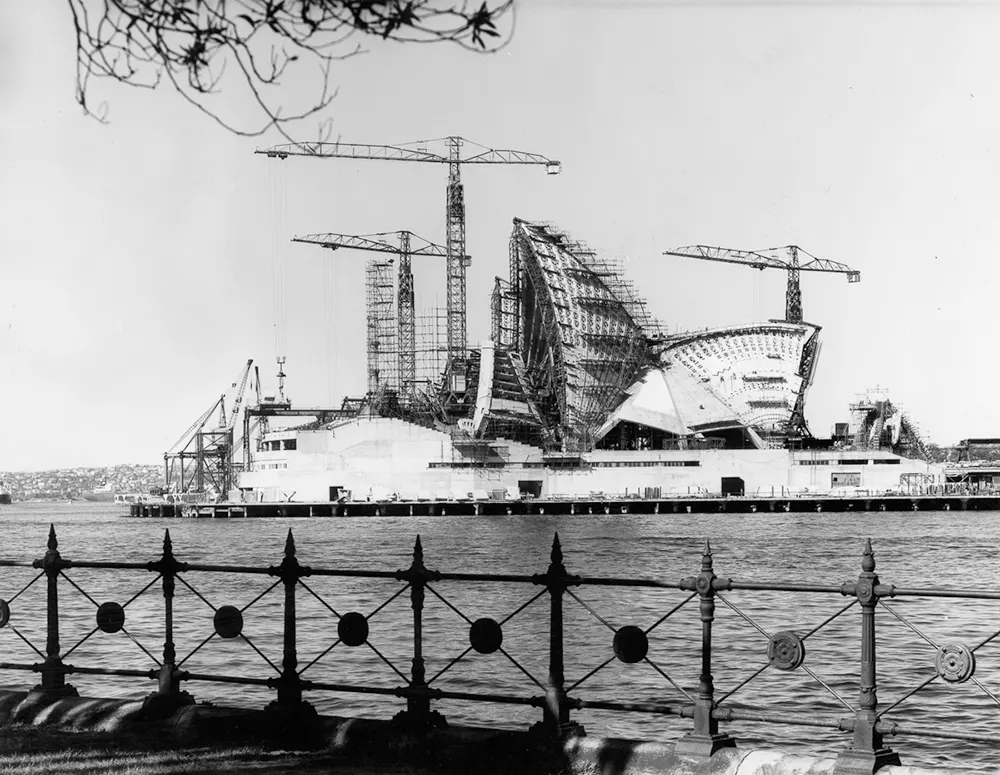

More than four years in, construction proceeds at a glacial pace.

Today the building is loved, yet while it was under construction attitudes were very different. The local press continually attacked its cost, its delays, and its architect; headline writers gave the now familiar white shell roof nicknames such as ‘the concrete camel’, ‘copulating terrapins’ and ‘the hunchback of Bennelong Point’.

Politicians tried to control the costs and speed up the programme. In 1966, the pressures reached such a climax that Utzon wrote to Davis Hughes, then Minister for Public Works in the New South Wales Government, saying ‘You have forced me to leave the job’. Hughes immediately accepted what he took to be the architect’s resignation.

Soon after Utzon left, Davis Hughes hired three local architects, Peter Hall, Lionel Todd, and David Littlemore, to complete the building which finally opened on 20 October 1973─six years behind schedule and costing more than ten times its original estimate.

The tram shed at Bennelong Point Circular Quay before the Sydney Opera House was built.

The facility features a modern expressionist design, with a series of large precast concrete “shells”, each composed of sections of a sphere of 75.2 meters (246 ft 8.6 in) radius, forming the roofs of the structure, set on a monumental podium.

The building covers 1.8 hectares (4.4 acres) of land and is 183 m (600 ft) long and 120 m (394 ft) wide at its widest point. It is supported on 588 concrete piers sunk as much as 25 m (82 ft) below sea level.

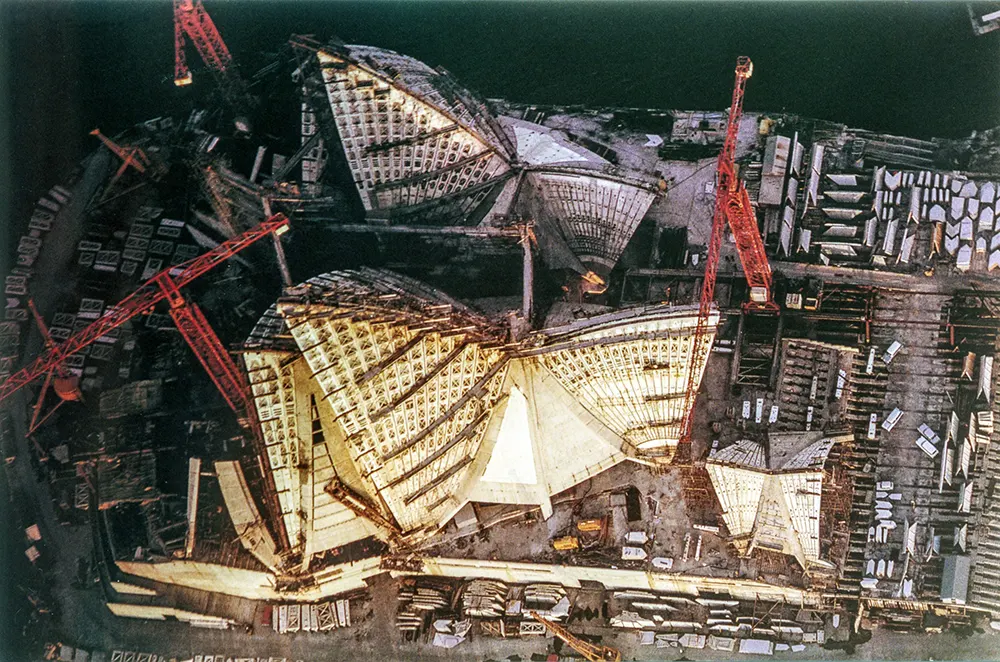

The highest roof point is 67 meters above sea level which is the same height as that of a 22-story building. The roof is made of 2,194 precast concrete sections, which weigh up to 15 tonnes each.

Although the roof structures are commonly referred to as “shells” (as in this article), they are precast concrete panels supported by precast concrete ribs, not shells in a strictly structural sense.

Though the shells appear uniformly white from a distance, they actually feature a subtle chevron pattern composed of 1,056,006 tiles in two colors: glossy white and matte cream.

The tiles were manufactured by the Swedish company Höganäs AB which generally produced stoneware tiles for the paper-mill industry.

Judges review entries in the design competition for the new Sydney Opera House.

Apart from the tile of the shells and the glass curtain walls of the foyer spaces, the building’s exterior is largely clad with aggregate panels composed of pink granite quarried at Tarana.

Significant interior surface treatments also include off-form concrete, Australian white birch plywood supplied from Wauchope in northern New South Wales, and brush box glulam.

The tram shed at Bennelong Point is demolished to make way for the construction of the Opera House.

The significance of the Opera House is not merely its iconic status. The building identified Utzon as a member of what Siegfried Giedeon called the ‘Third Generation’ of Modernist architects who sought a more plastic and more humane way of building.

It buried the Modernist concept that ‘form follows function’ and led the way for landmark cultural buildings. According to Frank Gerhy: ‘without his [Utzon’s] vision, there would hardly be the Guggenheim in Bilbao today’.

Utzon’s desire to push the boundaries of architecture wherever he could, meant that the building became a test bed for new technologies in construction.

His interest in the use of repetitive elements─what he called ‘Additive Architecture’─arising from the prefabrication of sections of the Sydney roof shells, was at the forefront of thinking about the manufacture of buildings.

The use of computers for structural design was in its infancy, but the roof shells could not have been done without them.

Computers were also used for the first time in the positioning of elements of the roof during construction. The use of epoxy resins for jointing precast concrete, sealants, laminated glass, and planar glazing had never been attempted before on such a scale.

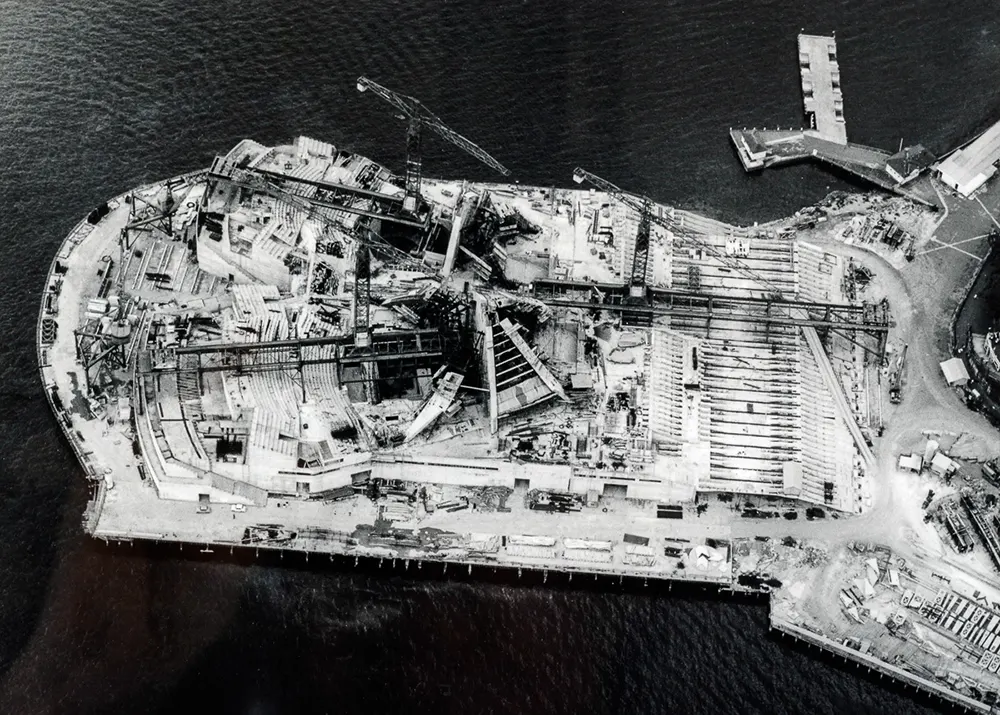

The site of the Opera House is prepared for construction.

In the late 1990s, the Sydney Opera House Trust resumed communication with Utzon in an attempt to effect a reconciliation and to secure his involvement in future changes to the building. In 1999, he was appointed by the trust as a design consultant for future work.

The Utzon Room: rebuilt under Utzon in 2000 with his tapestry, Homage to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. In 2004, the first interior space rebuilt to an Utzon design was opened and renamed “The Utzon Room” in his honor.

It contains an original Utzon tapestry (14.00 x 3.70 meters) called Homage to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. In April 2007, he proposed a major reconstruction of the Opera Theatre, as it was then known. Utzon died on 29 November 2008.

Tradesmen working on the construction of the Sydney Opera House live in caravans on-site at Bennelong Point.

The ocean liner “Canberra” passes the construction work on the Sydney Opera House.

By 1961, construction was running 47 weeks behind schedule.

The opera house begins to take shape after four years of work.

Podium structure complete, 1962.

Architect Utzon in front of the Sydney Opera House, eight years after his designed was selected and six years into construction.

Students protest and march from Sydney Opera House to Parliament House in Sydney after the resignation of architect Utzon.

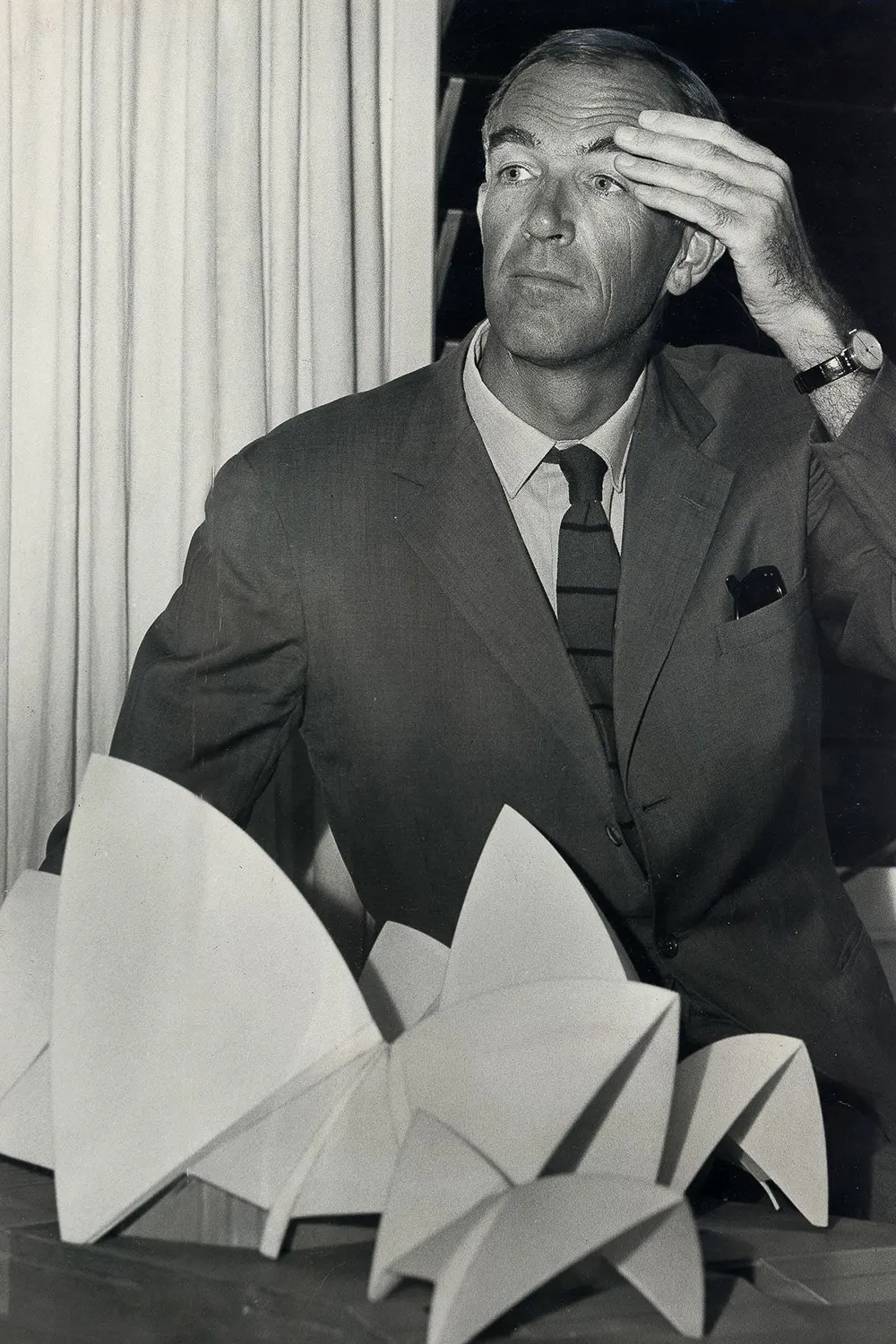

Architect Jørn Utzon after a press conference with a scale model of the Sydney Opera House.

While the exterior of the Opera House was mostly completed in 1966, the interiors had to be significantly redesigned after Utzon’s resignation.

Leading hand carpenter Norm Delmas of Ermington takes levels (left) as apprentice.

University of Sydney students armed with posters protest against the architects’ appointments for the Sydney Opera House, 20 April 1966.

The design-architect of the Sydney Opera House, Peter Hall, with a model of the building, 5 May 1968.

Mr R.Consigli, one of many architects consulting on the building of the Sydney Opera House, is pictured with a model showing the main halls of the Opera House as it will stand in its finished state, December 1969.

Design-architect Peter Hall, right, and R. Consigli with a model of the Sydney Opera House, 8 December 1969.

Shells structure, circa 1965.

The Opera House circa 1965.

Tiles complete, circa 1968.

Minister for Public Works Davis Hughes and Premier Robert Askin tour the concert hall of the Sydney Opera House during construction. Hughes had forced Utzon’s resignation five years earlier.

Sir Roden and Lady Cutler, and Sir Robert and Lady Askin with Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh at the opening of the Opera House.

The opening of the Opera House, 14 years after construction began.

View from the west.

The main Concert Hall during a performance.

The building illuminated at night.

The Opera House, backed by the Sydney Harbour Bridge, from the eastern Botanic Gardens.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Wikipedia / Australian Archives / Getty / The Saga of Sydney Opera House: The Dramatic Story of the Design and Construction of the Icon of Modern Australia by Peter Murray).